Suzanne Bowness, September 30, 2019

Photo credit: Luther Caverly, field photos courtesy of Dr. Tim Patterson

Earth Sciences Professor Tim Patterson devoted to safeguarding lakes in Canada’s north

Tim Patterson has spent many research hours in the past decade helping to boost awareness of the environmental composition of lakes in Canada’s north. With new funding from the Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) Clean Growth Program, the Earth Sciences professor is working on refining technologies that will help determine environmental baseline conditions, with the dual goal of helping partners in the mining sector meet environmental regulations and increasing general awareness about the health of lakes and ecosystems.

The three-year project will focus on lakes in the Yellowknife region of the Slave Geological Province, central Northwest Territories, an area that’s home to several promising sites for future mines. Building on technology already developed by his research team, Patterson’s new project aims at refining a method of testing lake sediment to measure its historical composition including the presence of any harmful elements such as arsenic (one of the most common harmful mining byproducts in the north). A second component of the project will provide more precise quantitative analysis of lake histories.

For mining companies like project partner TerraX Minerals, the research has potential to help improve the speed and accuracy by which they can meet the Mine Site Reclamation Policy (MSRP) set out by the government of the Northwest Territories. The policy requires companies to have a remediation plan in place even before starting on a mining project to ensure that ecosystems are returned to a state comparable to their original condition. The challenge is in determining that baseline, particularly in light of legacy contamination from earlier mining ventures such as Giant Mine near Yellowknife, NT, in operation from 1948 to 2004, and because there are naturally elevated levels of metals of concern, such as arsenic, in many lakes in the region.

Because the spring and summer seasons are so short in the north, lakes are often only “productive” for a short window each year, meaning that the sediment deposited each year is often only a few millimeters thick. As a result, conventional “gravity cores” frequently used in studies aimed at measuring background, pre-industry conditions, are often inadequate. Instead, “freeze cores” filled with dry ice are used to freeze a perfect record of the sediment. An instrument called an Itrax XRF core scanner is then used to analyze the cores to 0.1 mm resolution to detect very subtle historical changes in the environment.

Yet the Itrax scan can take hours, currently longer than the frozen cores can remain frozen – so the first task is to figure out a refinement to an existing containment vessel that the Patterson team has developed, that will permit longer segments of core to remain frozen for over 20 hours and also meet the additional compatibilities demanded by the precision scanner, which is sensitive to the by-products of thawing, such as condensation.

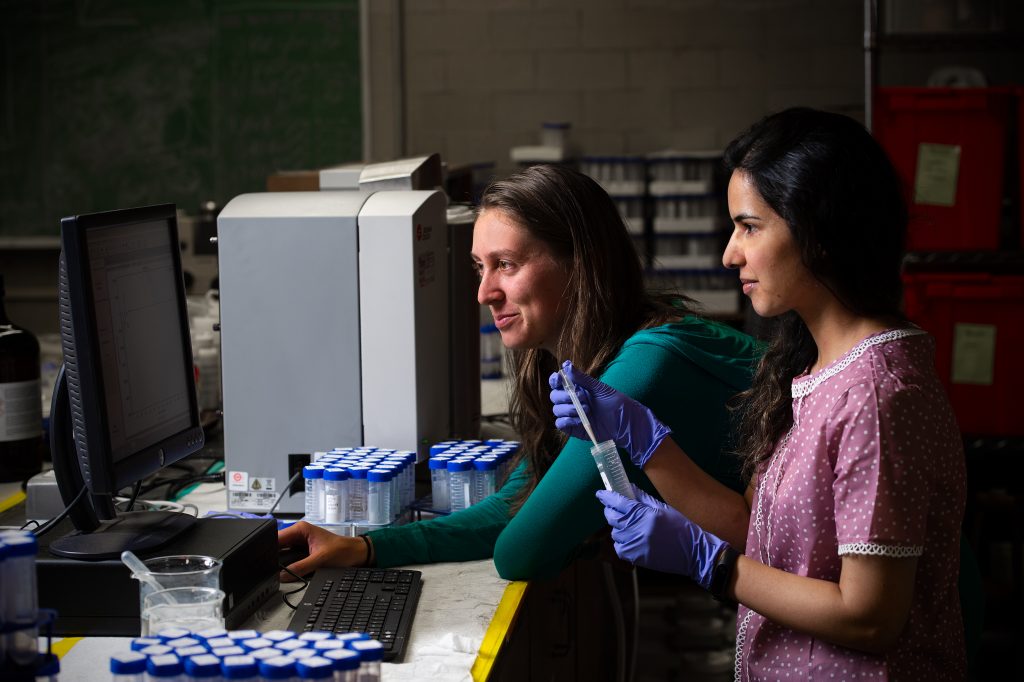

A second phase of the project will focus on improving the quantitative geochemical analysis of the materials, required by regulators. PhD students Braden Gregory and Nawaf Nasser (above) are already at work on this phase of the project using mathematical algorithms and calculations. Two newly arrived graduate students Naomi Weinberg and Aisha Amanullah (below) will be furthering this research.

A professor at Carleton since 1988, Patterson’s lab currently oversees several undergraduates, 11 graduate students and two postdoctoral researchers. Other recent and ongoing projects include a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) Strategic Project grant-supported investigation of the long-term viability of the world’s longest ice road, the 588 km Tibbitt to Contwoyto winter road in the Northwest Territories, remediation of lakes in Canada’s north, the effects of runoff from road salt in terms of causing degradation to lakes in eastern Canada. Most recently, Patterson is part of a team to have sediments in Crawford Lake near Milton Ontario recognized as the ”golden spike” for the newest proposed geological epoch, the Anthropocene.

For all of these projects, Patterson says collaboration is key, both at Carleton and with other partners. For his current project, Patterson is working closely with Steve Tremblay, director at the Carleton’s Science Technology Centre to brainstorm solutions for developing a containment vessel to keep freeze cores frozen. He also collaborates with former PhD student Eduard Reinhardt, now a professor at McMaster University which owns one of only two Itrax scanners in Canada, and collaborates closely with former PhD student Jennifer Galloway of the Geological Survey of Canada in Calgary. He also liaises regularly with Carleton Earth Sciences graduate Hendrik Falck who works as a mineral deposits geologist with the Northwest Territories Geological Survey. He furthermore credits his mining company partners and the North Slave Métis Alliance and other indigenous partners for providing support in field research in the north.

Patterson says he was first drawn to this work growing up on and around the lakes of southern New Brunswick. As he deepened his research interests in lakes, seeing the effects of past disregard for environmental stewardship made him want to be part of the solution for the future.

“I was just blown away by the environmental degradation that had occurred in the past,” he says of learning about the effects of past mining projects in many parts of Canada and around the world, in an era before people appreciated how fragile lake ecosystems were. “No one wants that sort of mess again. I want to make sure that lakes in Canada’s north and elsewhere remain as pristine as they can be, while still permitting sustainable development of mines and other industries that are of such critical importance to the Canadian economy.”

Share: Twitter, Facebook